The World Wide Web celebrated its 28th birthday on March 12, 2017. The web’s inventor and founder, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, wrote an open letter expressing his increasing concern about three new trends, which he believes “we must tackle in order for the web to fulfill its true potential as a tool which serves all of humanity.”

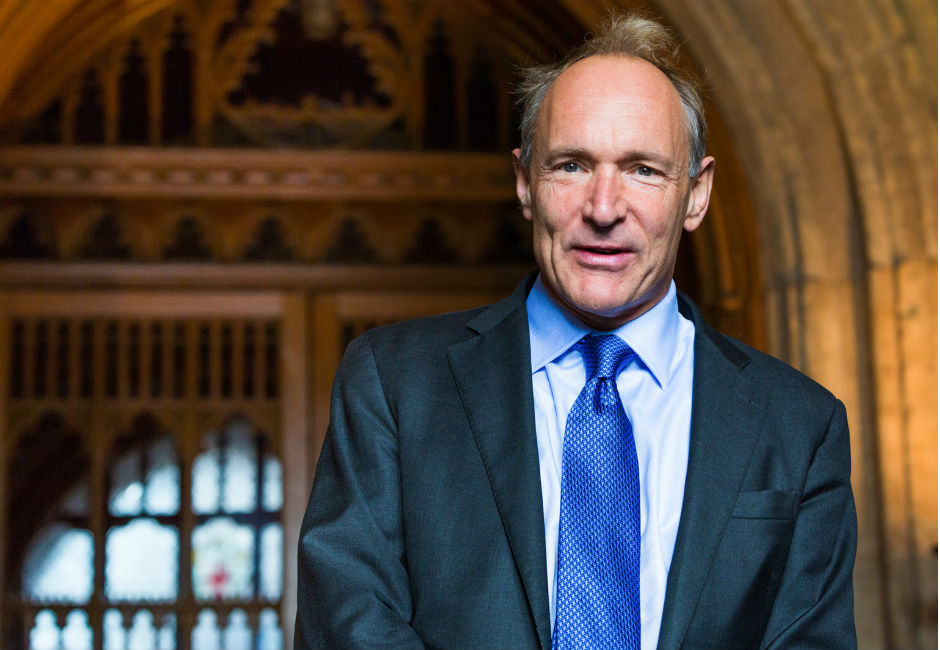

Sir Tim Berners-Lee arriving at the Guildhall to receive the Honorary Freedom of the City of London. Photo courtesy of Paul Clarke via Simple Wikipedia.

New Trends of the World Wide Web

Sir Tim Berners-Lee submitted his original proposal for the World Wide Web 28 years ago. According to Sir Tim, he imagined the web as an open and balanced platform that would allow people throughout the world to share information, gain access to opportunities, and work together across cultural and geographic boundaries.

In many ways, the World Wide Web has lived up to his vision. However, over the past 12 months, Sir Tim has become increasingly worried about three new trends, which he believe we must deal with in order for the web to fulfill the its true potential as a tool which serves all of humanity.

1.) We have lost control of our personal data

Currently, the business model for many websites offers free content in exchange for our personal data. Many of us agree to offer our personal information. We readily accept long and confusing conditions and terms.

Many of us don’t mind some of our personal information being collected in exchange for free services. However, Sir Tim points out we’re missing a trick.

“As our data is then held in proprietary silos, out of sight to us, we lose out on the benefits we could realize if we had direct control over this data, and chose when and with whom to share it. What’s more, we often do not have any way of feeding back to companies what data we’d rather not share — especially with third parties — the T&Cs are all or nothing.”

This widespread and extensive collection of our personal information by companies also has additional impacts. Through partnership, or coercion of companies, governments are increasingly watching every move we make while we’re online. Sir Tim says this tramples on our rights to privacy.

In tyrannical and authoritarian regimes, it’s clear to see the harm that can be caused. Political opponents can be monitored and bloggers can be arrested or killed.

Sir Tim elaborates on the added impact.

“But even in countries where we believe governments have citizens’ best interests at heart, watching everyone, all the time is simply going too far. It creates a chilling effect on free speech and stops the web from being used as a space to explore important topics, like sensitive health issues, sexuality or religion.”

2.) It’s too easy for misinformation and ‘fake news’ to spread on the web

Today, most people find information and news on the World Wide Web through only a handful of search engines and social media sites. And these sites make more money when we click on the links they show us.

Sir Tim wrote about how search engines and social media sites choose what to show us based on algorithms, which learn from our personal data that they’re constantly harvesting.

“The net result is that these sites show us content they think we’ll click on — meaning that misinformation, or ‘fake news’, which is surprising, shocking, or designed to appeal to our biases can spread like wildfire. And through the use of data science and armies of bots, those with bad intentions can game the system to spread misinformation for financial or political gain.”

3) Online political advertising needs understanding and transparency

Political advertising on the World Wide Web has quickly become a sophisticated industry. Since most people get their information from just a few platforms — and the ever-increasing complexity of algorithms that draw upon vast pools of our personal information, political campaigns are now building individual advertisements targeted directly at users.

Sir Tim noted a recent political campaign that used this technique.

“One source suggests that in the 2016 U.S. election, as many as 50,000 variations of adverts were being served every single day on Facebook, a near-impossible situation to monitor. And there are suggestions that some political adverts — in the U.S. and around the world — are being used in unethical ways — to point voters to fake news sites, for instance, or to keep others away from the polls. Targeted advertising allows a campaign to say completely different, possibly conflicting things to different groups. Is that democratic?”

Solutions to Complex Problems

According to Sir Tim Berners-Lee, these are complex problems, and the solutions won’t be simple. Nevertheless, he points out that a few broad paths to progress are already apparent.

We have to work with web companies to initiate a balance that puts a fair level of data control back in the hands of people. Additionally, we must fight against government over-reach in surveillance laws.

We must also push back against misinformation and fake news by encouraging gatekeepers like Facebook and Google to continue their efforts to combat the problem, while avoiding the creation of any central bodies to decide what is “true” or not.

More algorithmic transparency is necessary to understand how important decisions that affect our lives are being made — and perhaps a set of common principles to be followed. We urgently need to close the “internet blind spot” in the regulation of political campaigning.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee wrote that he may have invented the World Wide Web, but all of us have helped to create what it is today. All the web pages, tweets, posts, blogs, applications, videos, photos, and more represent the contributions of millions of us around the world building our online community.

Last year, we saw Nigerians stand up to a social media bill that would have hindered free expression online, protest and popular outcry at regional Internet shutdowns in Cameroon, and large public support for net neutrality in both the European Union and India.

Sir Tim adds, “It has taken all of us to build the web we have, and now it is up to all of us to build the web we want — for everyone.”

Sir Tim Berners-Lee’s open letter is available en français, en español, em português and بالعربية.

Featured image courtesy of Paul Clarke via Simple Wikipedia | Cropped and Resized | CC BY-SA 4.0