Ocean plastics are found from the Antarctic to the Arctic. In every marine environment, scientists have found plastic.

As the amount of plastic litter continues to spread, managing this pollution has become a rapidly increasing serious issue of global concern.

Some estimates claim plastics consist of 50 to 80 percent of the litter in the oceans. Although other human-generated debris is likely to rot or rust away — plastics can endure for years.

The shore of Kamilo beach, on the tip of Hawaii’s Big Island, is a prime example of how a tranquil and calm tropical beach becomes destroyed. (Photo courtesy of Bob Daemmrich/Polaris/eyevine)

Struggling With Ocean Plastics

For years, people have been hearing stories about ocean plastics in the ‘Great Pacific garbage patch’ — areas of the central Pacific Ocean where plastic particles accumulate. Though volunteers have been participating in cleaning up beaches across the globe, research is rapidly falling behind public concern.

Additionally, scientists have been struggling to answer the most basic questions about ocean plastics:

- How much plastic is in the oceans?

- Where is all of the plastic?

- In what form is the plastic debris?

- What harm is ocean plastic doing to the planet and humanity?

It’s hard for scientists to answer these questions because science at sea is difficult, time-consuming, and expensive. In addition, it’s extremely challenging to survey vast oceans at length because it involves locating and compiling data of small — sometimes-microscopic — plastic fragments.

There’s no doubt — humans have dumped a vast amount of plastic debris into the world’s oceans. And the shore of Kamilo beach, on the tip of Hawaii’s Big Island, is a prime example of how a tranquil and calm tropical beach becomes polluted and destroyed.

Kamilo beach cannot be reached by road. It has white sand and powerful waves. But this once pristine beach is faced with one certain issue — it’s carpeted with ocean plastics.

Due to a combination of ocean and local currents, tons of bottles, toothbrushes, ropes, and fishing nets washed up on the shoreline. In 2011, researchers reported that the top sand layer of the beach could be up to 30 percent plastic by weight. Today, Kamilo beach is one of the dirtiest beaches on earth.

Serious Issue of Growing Global Concern

Environmentalists and scientists realize more work is necessary to fight plastic pollution. Last year, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) passed a resolution at its Nairobi meeting, stating the following:

“The presence of plastic litter and microplastics in the marine environment is a rapidly increasing serious issue of global concern that needs an urgent global response.”

Nevertheless, every year, global production of plastics continues to rise. Today, it is up to around 300 million tonnes. Sooner or later, much of this plastic eventually ends up in the ocean. Plastic garbage is left on beaches, and plastic bags blow into the ocean. If landfills are not managed properly, large quantities of plastics dumped in waste sites will simply blow away.

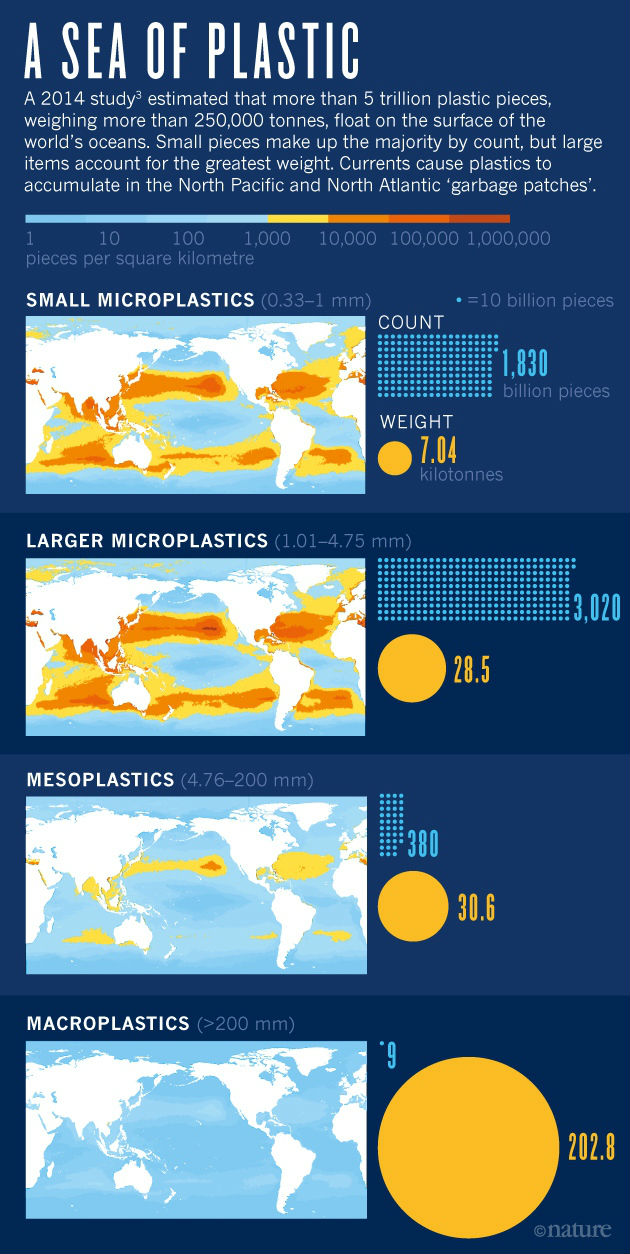

In a 2014 paper, a team of researchers and Marcus Eriksen, director of research and co-founder of the 5 Gyres Institute in Santa Monica, California, published data they analyzed on items they found in voyages taken across the world’s oceans.

While stressing that their “minimum estimates” are “highly conservative” the researchers suggest there is more than five trillion plastic pieces weighing more than 250,000 tonnes afloat at sea.

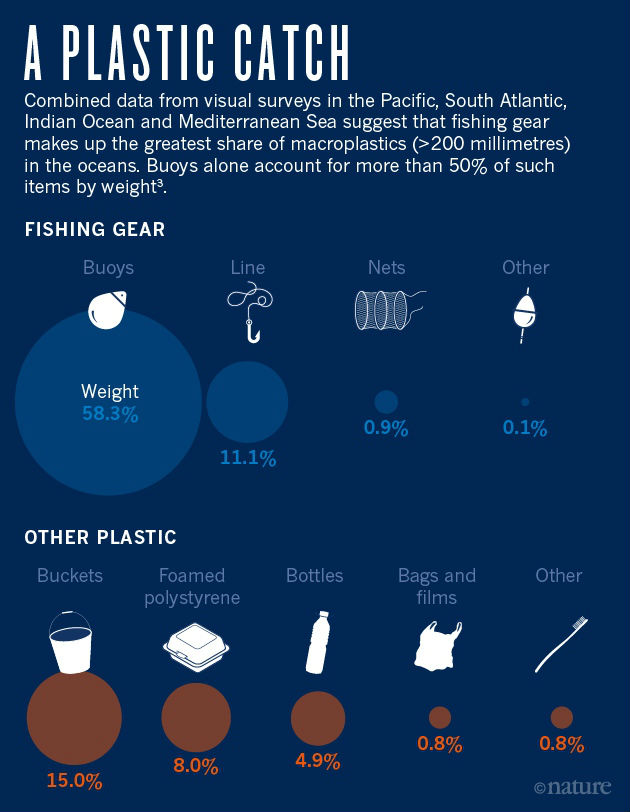

The list of ocean plastics includes bottles, buoys, buckets, nets, bags, and lines. Sunlight and waves break down many plastic items until they reach microscopic sizes.

Additionally, other plastics start out small in size — such as the ‘microbeads’ that are added to cosmetic products and face scrubs. These microbeads end up going down the drain.

Marine Plastics Kill Hundreds of Animals Species

Concerned global citizens know that marine plastic can harm animals. Lost, dumped, or abandoned fishing gear has trapped and killed hundreds of animal species — from birds to turtles to seals. And many organisms swallow pieces of plastic, which can accumulate in their digestive system.

One often-quoted figure cites that close to 90 percent of seabirds — called fulmars — washed ashore dead in the North Sea. The fulmars had plastic in their guts.

One of the first studies to show a direct link between plastic and fertility problems discovered that animals — in water laced with plastics — had poorer-quality eggs and sperm and produced 41 percent fewer larvae than did those in a control group.

In June, another study performed by fish ecologists Oona Lönnstedt and Peter Eklöv; found that when they exposed perch larvae to ‘environmentally relevant’ concentrations of microplastics, the larvae ate the plastics.

It appeared as though the larvae prefer the microplastics to actual food. This eventually led them to grow more slowly and fail to respond to lingering predators. After spending 24 hours in a tank with a predator, only 34 percent of plastic-dosed larvae survived — compared with 46 percent of those raised in clean water.

Finding a Solution

Even though there is a lack of complete data about ocean plastics, many researchers agree that humanity should not wait for more evidence before taking action.

A non-profit Dutch foundation called The Ocean Cleanup has devised a way that deploys a 100-kilometre-long floating barrier in the Great Pacific garbage patch. By 2020, the group claims the floating barrier will remove half of the surface plastic there.

However, this well-meaning project has been met with skepticism. Skeptics say that plastic in the gyre is so dilute that it will be very hard to scoop it up. They add that they’re concerned that the barrier will disturb fish populations and plankton.

Nevertheless, chief executive of The Ocean Cleanup, Boyan Slat, welcomes the criticism. He says the barrier project is still in an early phase, with a prototype currently deployed off the Dutch coast. He adds, “We’re using this test as a platform to investigate whether there’s any negative consequences. The only way to find out is to go out and do it.”

Surveying Areas Never Explored

Surveying the ocean for plastic on the surface waters is difficult and expensive. But it’s even harder to survey the depths of the world’s oceans. Researchers are unable to get plastic samples from the vast deep seas that have never been explored — like the ocean floor.

It will be a pain-staking and extremely costly endeavor to survey all these areas. The level of concentration is so dilute that scientists would have to test enormous volumes of water to get reliable results. Instead, right now researchers can only make estimates.

Jenna Jambeck researches waste management at the University of Georgia in Athens. Last year, Jambeck led a team that published a report estimating the amount of waste coastal countries and territories generate. The team also estimated how much of that could be plastic that ends up in the ocean.

The group reached a figure of 4.8 million to 12.7 million tonnes every year — equivalent to nearly 500 billion plastic drinks bottles. However, her estimate excluded the plastic that is lost or dumped at sea, and all the plastic that is already there.

Trawling for Plastic Debris

Some researchers have gone trawling — using fine-meshed nets to see what plastic they can drag up. Last year, oceanographer Erik van Sebille of Imperial College London and his colleagues published one of the largest collections of trawling data.

They combined information from 11,854 individual trawls, from every ocean except the Arctic. The data shows a ‘global inventory’ of small plastic pieces floating at or near the surface.

In 2014, the inventory consisted of estimates that were between 15 trillion and 51 trillion pieces of microplastic floating in the oceans, with a total weight of 93,000 to 236,000 tonnes. But this estimate of total surface plastic is just a small fraction of what Jambeck estimated entered the ocean every year.

It’s unclear to researchers and scientists where the remaining ocean plastics are. “That’s the big question,” says Jambeck. “That’s a tough one.”

Improve Waste Management and Recycling

Earlier this year, van Sebille and his colleague Peter Sherman showed that it would be much more effective to place clean-up equipment near the coasts of China and Indonesia, where much of the plastic pollution originates.

According to van Sebille, “The closer to the plastic economy loop you intervene the better it is. We’ve got to stop it in the treatment plants, in the landfills. That is the point to intervene.”

Eriksen compares cleaning up plastic pollution to addressing air pollution. People have finally realized that filtering the air is not a long-term solution. Filtering the oceans seems equally questionable, he says. “What we’ve seen worldwide is you go to the source.”

That means reducing plastic use, improving waste management, and recycling materials to stop them from ever reaching water.

Featured image courtesy of Forest and Kim Starr via Flickr | Cropped and Resized | CC-BY-SA-2.0